Is It Too Much to Ask for a Third Way Beyond Free Trade and Constrained Trade?

Trade policy should focus first and foremost on defense, dual-use, and enabling sectors and largely ignore nonstrategic sectors.

Globalism has failed America. Few nations have been as open and committed to free trade as the United States, which has meant firms in most nations have had unfair advantages over firms in America as they have to various degrees closed their markets and unfairly supported their domestic industries.

The dollar’s status as the reserve currency has meant currency adjustment cannot play its natural role in balancing trade. And U.S. free trade ideology and global trade rules have constrained the United States from putting in place robust industrial policies. For globalists, no industry is more important than any other, and any and all results from globalization are by definition optimal. The result has been a decline of the U.S. manufacturing sector, especially in technologically advanced traded-sector industries.

Given that failure of the globalist, free-trade vision, it’s not surprising that there has been a Jacobian reaction to it, as we now see with President Trump’s manufacturing protectionism. U.S. Trade Representative Jameson Greer exemplified this when he laid out the administration’s three trade goals: reducing the trade deficit, boosting manufacturing, and reshoring “our economy.”

To be sure, those who adhere to the free trade consensus have ignored all three. They deny the trade deficit is a problem. They believe that manufacturing is no better than any other sector. And they favor offshoring because it lowers prices.

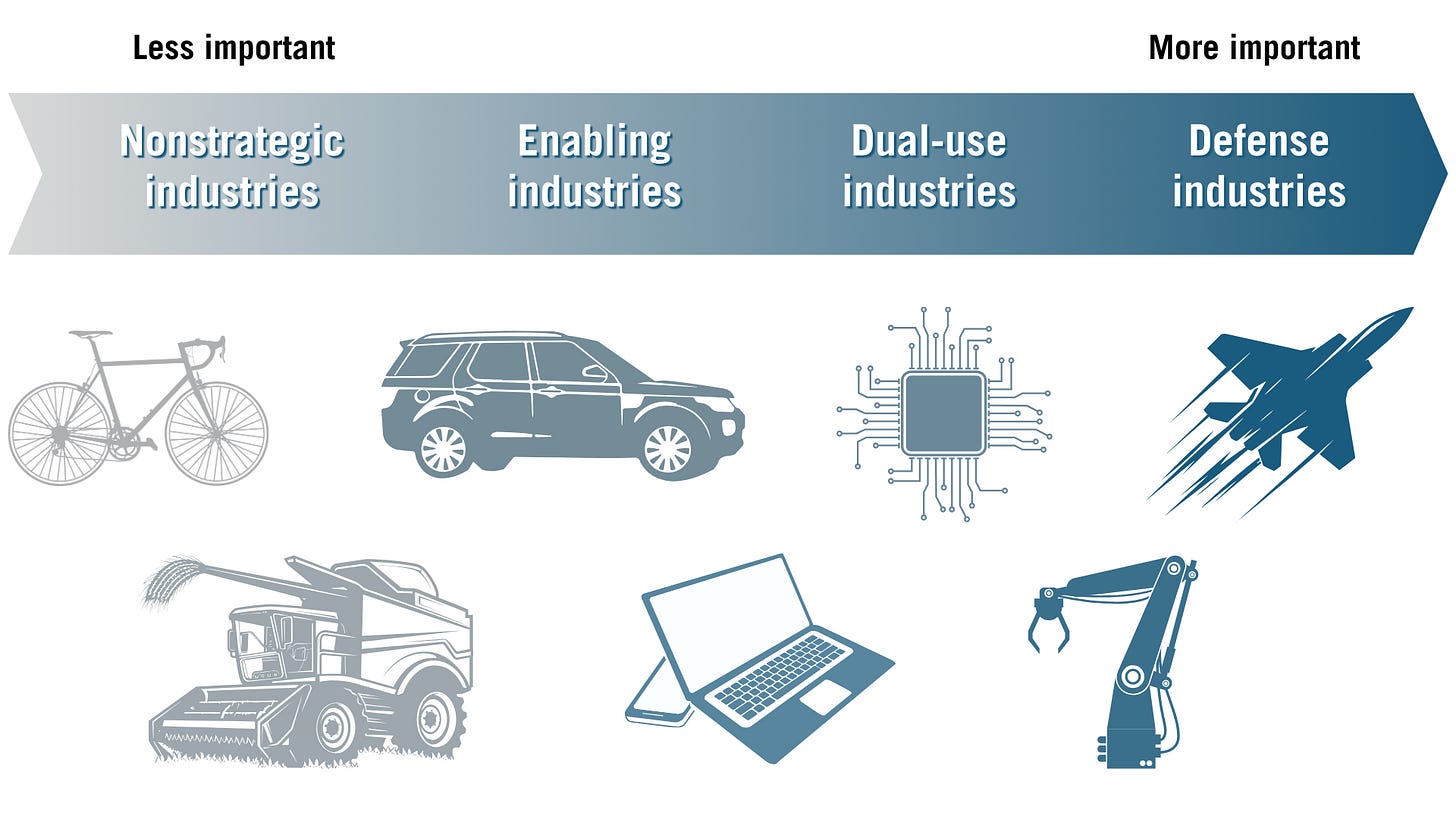

But overreaction always goes astray, and it has been no different in this case. What America needs is a “third way” for trade policy that is grounded in the realization that some industries contribute more to national power and therefore matter far more than others. This can be viewed as a continuum from nonstrategic industries on one end of the scale to defense industries on the other end, with enabling and dual-use industries in the middle.

Defense includes industries like ammunition, guided missiles, military aircraft, defense satellites, and others that contribute to national power in obvious ways: Not having world-class innovation and production capabilities in these industries would weaken the country’s military capabilities. Policymakers across the ideological spectrum agree that these industries are strategically important and that market forces alone will not produce the needed results.

At the other end of the scale are industries that have little to do with national power. These include furniture, coffee and tea manufacturing, bicycles, carpet and rug mills, window and door production, plastic bottle manufacturing, lawn and garden equipment, sporting goods, jewelry, caskets, toys, running shoes, etc. If worst came to worst and adversaries such as China gained dominance in any of those industries and decided to cut us off, we’d survive. In part, because none of them are critical to running the U.S. economy; many produce final goods that might inconvenience consumers to do without, but they wouldn’t cripple any other industries. Moreover, it would be relatively easy to start or expand domestic production of them, because none of them are very technologically complex from a product or process perspective, and the barriers to entry are relatively low. Farming, oil and gas, and most mining falls into this category because the United States can easily expand them if need be.

Next to defense industries on the continuum are dual-use industries, which are critical to American strength. Losing aerospace, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, semiconductors, displays, advanced software, fiber optic cable, telecom equipment, machine tools, motors, measuring devices, and other advanced sectors would give adversaries incredible leverage over America. Merely threatening to cut off our access to them (assuming our allies have also allowed themselves to deindustrialize in these sectors) would immediately bring us to the bargaining table. Companies in dual-use industries also tend to require global scale to be competitive. Moreover, many dual-use industries produce intermediate goods like semiconductors, so being cut off from them would cripple many other industries. These industries are hard to stand up once they’re lost because of the complexity of their production processes and because of the industrial commons that support them. They also support defense industries.

The last type of industry on the continuum is enabling industries. If the United States was cut off from these industries, the immediate effects on military readiness would be small. And the U.S. economy could survive at least for a while without production. But because these industries require technological research and development, process innovation, and skills, losing them would have negative implications for both defense and dual-use industries. Enabling industries contribute to the industrial commons that support dual-use and defense industries. The best case in point is the automobile sector. A severely weakened motor vehicle sector would weaken the tank production ecosystem. Similarly, a weakened commercial shipbuilding sector would weaken military shipping. A weakened consumer electronics sector weakens military electronics. And so on.

As such, trade policy should focus first and foremost on defense, dual-use, and enabling sectors and largely ignore nonstrategic sectors. The problem is that Trumpian economic nationalism sees all four types of industries as equally worth protecting. Why else would Trump fight Canada so hard for trading advantage in dairy and wood products? Both are clearly nonstrategic sectors. Likewise, why else would the administration push so hard to promote exports of natural gas and farm products? Boosting exports of the former will reduce American fossil fuel resources, boosting exports of the latter will do little to increase American food security.

A second problem with Trump’s trade approach is that because the central challenge is about limiting China’s techno-economic power over the West, then what really matters is ensuring the West, not just America, has the necessary capabilities. And that depends in part on keeping allies in the tent so we can challenge China collectively. It also means we should trade more trade with key allies, not less.

Finally, by focusing on manufacturing and the trade deficit, Trump could very well make progress on both but at the cost of hollowing out strategic industries. For example, America could reduce its trade deficit with more gas and food exports. We could grow manufacturing by expanding nonstrategic industries. But advanced industries could continue to decline, and there is no particular reason why tariff walls will prevent that from happening.

What really matters are strategic industries (including defense). America doesn’t have much time left before our strategic-industry base declines to a point of no return. It is not yet too late to reorient trade and industrial policy to counter China by bolstering America’s most strategically important defense and nondefense industries. But we are late in the game, and time is running out.

Excellent and important commentary again, and your call is in urgent need of support by US policymakers.

Your “third way” and distinguishing between industries is an excellent way to make clear that not all things are equal, and that is an important starting point.

As I and my classmates were told early in our political science education: we would not get far in the field until we started to understand that one opinion is not necessarily as good as the next.

One industry or technology is not necessarily as important as the next; you are exactly correct. Nor is one economic policy as good for a nation’s long-term survival and security as the other. America for too long has been favoring a consumption-based economy, where a focus particularly on consumerism has prompted our economic planners and corporate sector to seek “victory” by finding a supplier that could provide the most for Americans to consume at the lowest possible per-unit cost. We found such a supplier in China, after flirting with the idea that Mexico could after entering NAFTA in the early 1990s.

Of course, there is more to China’s role as a supplier, as communist parties such as the one that rules China were built to find opponents’ weaknesses and exploit them, while giving us - as it said - the rope to which we could hang ourselves. Beijing has been more than happy to pursue a mercantilist economic policy by limiting consumption at home while aggressively ensuring US manufacturing moved from America to China, so the country could export anything and everything to the US. One only needs to look out China’s foreign exchange holdings and how they ballooned after China’s entry into the WTO in 2001.

Part of this belief in consumerism rested upon that American brands would also be the leaders. We didn’t learn the lessons of the automobile industry, when American buyers began to value less long-established brands such as Ford, GM, Chrysler and others and instead purchased new, foreign brands, such as Toyota and Honda. The nations that use to supply us moved up the value change, from OEM to ODM to finally OBM, and China has always had this goal, as well as the ability to transition in that direction.

Along with policymakers being prompted to understand the importance of industrial policy - another of your all-important recommendations - and the difference in importance of the various industries and technologies, US policymakers must also realize the debilitating effects of an economy that focuses on short-term consumption, the kinds of industries we support, our deficit, our both our trade policy and foreign policy, and, most importantly, our national security, given to whom we have ceded our productive, research and technological capabilities.

In addition to placing different weightings on the various industries and their importance to American’s manufacturing, innovation and security, it will be critical that US economic policy once again understands that there has to be a better balance between production and consumption being done in America. As you have argued well, not all industries will be needed to be brought back on shore; we don’t need to be making t-shirts and other labor-intensive goods. However, there are pitfalls with an economic model that focuses on consumption of so much being made offshore and less on savings, and we see it in our trade deficit.

Thanks again.